Welcome to Card Game DB

Register now to gain access to all of our features. Once registered and logged in, you will be able to create topics, post replies to existing threads, give reputation to your fellow members, get your own private messenger, post status updates, manage your profile and so much more. If you already have an account, login here - otherwise create an account for free today!

Register now to gain access to all of our features. Once registered and logged in, you will be able to create topics, post replies to existing threads, give reputation to your fellow members, get your own private messenger, post status updates, manage your profile and so much more. If you already have an account, login here - otherwise create an account for free today!

Crafting The Theory - The Effects of Valar

Jul 10 2012 05:00 PM |

Kennon

in Game of Thrones

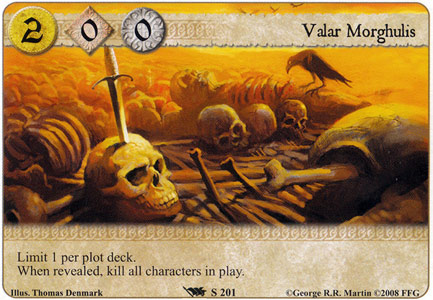

Small Council Crafting the Theory Kennon Last month in Crafting the Theory, we examined Valar Morghulis under the lens of what it does for you, and the different varieties of advantage that it provides. This month, we’re going to reverse things and examine this most controversial of plots from the angle of what it does to your opponent and then move on to how this interacts with the game as a whole.

Last month in Crafting the Theory, we examined Valar Morghulis under the lens of what it does for you, and the different varieties of advantage that it provides. This month, we’re going to reverse things and examine this most controversial of plots from the angle of what it does to your opponent and then move on to how this interacts with the game as a whole.When you play Valar Morghulis (Core), you’re generally concerned with some combination of generating card advantage, buying time, or killing a specific character, but what concerns does this generate for the opponent facing the Valar?

- Play style

- Deck construction

When playing, most players must be extremely conscious of the possibility of an incoming Valar Morghulis and what this might do to their plans. Thus, they are generally forced to tailor some level of their gameplay in order to account for this possibility. Most often this amounts to something like holding back and not playing Arianne Martell and Myrcella Lannister when you’re already ahead in on character count with 4 to the opponent’s 2. The reason for this is that this becomes a prime opportunity for the opponent to utilize their Valar to generate considerable card advantage, per Part 1. By holding back on these additional characters, you lessen the possibility of extreme card advantage from an opposing Valar Morghulis and since most competitive players actively attempt to maximize the impact of their plays, you also minimize the possibility of the opponent revealing Valar during the next plot phase. Will it dissuade them entirely? Possibly not, but you do at least make it less tempting.

Now the particularly astute may note that the above example with Arianne and Myrcella is actually an example of a tactical play in the particular situation, but again, that’s mainly for ease of discussion. The important factor to consider is that you must actually take these numbers and possibilities into consideration during each turn until Valar Morghulis is revealed (and possibly past then as well if there’s a chance that plots may recycle again). Having to make this analysis every turn and decide what rate of character play allows you to maintain the competitive edge over your opponent without overextending and creating a situation where the card advantage of revealing Valar is so tempting that your opponent uses it modifies your style of play and thus your strategy for the rest of the game. By and large, that’s not to say that it only applies to a single match, either. Ask any player with a moderate to advanced level of experience in the game and they’ll tell you that their interactions with Valar have so permanently altered their play that they look to account for the possibility of its reveal in every game that they play for the rest of their time with A Game of Thrones.

The possibility that your characters may die to an incoming Valar Morghulis that you’re not strictly able to predict also alters the way that players build decks, which most certainly alters their strategic space. The presence of such a universal kill effect generally forces deck construction in one of two directions.

In one case, players may take the option of minimizing the possibility of dead draws. What this means is that they generally only play one copy of unique characters in their decks so that if the character is inadvertently killed, they have no possibility of later drawing another copy of that character which they will be unable to play, thus making that card slot and that draw completely wasted. The no-duplicate option mitigates the issue from a deck construction level by ensuring that once in the game, all of their characters are as equally vulnerable. This route is most frequently taken by control decks, as they are attempting to maximize their redundancy through draw, as you may remember from an early entry in Crafting the Theory.

In the other case, decks may attempt to compensate for the possibility of a universal kill effect by building contingency plans into the deck which then work to mitigate Valar through gameplay once they’ve been drawn. This can be a done by utilizing duplicates and other saves as well as return to play and Cannot be Killed effects. One of the prime examples of a deck like this is the archetypal Baratheon Noble Rush build. In this build, players general include the maximum number of duplicates of the key unique characters in order to maximize their chances of having the appropriate duplicates in play in time to use their save effects when their opponent reveals Valar Morghulis, which is directly related to redundancy through efficiency as detailed in the same earlier Crafting the Theory. The same Noble Rush deck also uses The Power of Blood in order to mitigate Valar by giving their characters the “Cannot be Killed†keyword, but again this relies on timing in the course of the game rather than strictly within deck construction.

Valar Morghulis and the Design of the Game

With the effect on the opponent out of the way, I want to turn our attentions to Valar in the context of balance in the game as a whole. It probably doesn’t come as a surprise to most who know me that I certainly defend the presence of Valar in the environment to my dying day. In order to really understand how instrumental it is in the functioning of the game as a whole though, we must examine several different pieces of the core mechanics of the game.

The first mechanic that we have to examine is draw. Though it’s not strictly a core mechanic beyond the framework draw 2 each turn, it has also become so ingrained that you’ll find a multitude of options for additional draw in each house and through neutral cards. The explosion of additional means to draw leads most decks to have some strong capability to continually apply pressure to the table while refilling their hands so that it can be quite rare to completely run out of steam from an inability to keep cards in hand to use. In some cases, in fact, the ability to draw exceeds the ability to play the cards in hand, which leads to ever expanding hand sizes and vastly increased options. The lack of a maximum handsize in the core mechanics of the game means that the only theoretical limit on hand size and options is the size of your deck.

The next mechanic to examine is the resource system of AGoT. For comparison purposes, we’re once again going to talk about another game- MtG. In Magic, you start with 0 resources in play and as a game mechanic, are limited to playing one land per turn. This means that barring card effects, the number of lands that you have available to you and thus resources (each land produces 1 resource) follows a generally linear progression. If we discount the effects of random draw, then on turn one you’ll have 1 resource and scale upward to have 5 resources on turn five and so on. If you’re particularly curious, you can take a look a rather detailed article here (http://magic.tcgplay...int.asp?ID=3096) that will illustrate a variety of land drop and random draw interactions in MtG using hypergeometric distributions and the like. Suffice it to say that with the single card drawn each turn in MTG and the random distribution of land cards in your deck, you won’t have the perfect draw necessary to always play a land every single turn.

In AGoT on the other hand, the resource system is not so straightforward. While many players, including myself, laud the plot card mechanic of the game and the capability that it gives you to dictate how your turn goes, this actually complicates the resource mechanic considerably. While it’s much more user friendly to be able to pick the plot with the appropriate amount of gold for what you need to accomplish that turn, it makes things actually much more difficult from the perspective of the card designers and developers. In a game like MtG with a loosely linear progression of resources, the power level and effects of cards can scale in direct relation to the cost, while the R&D can be relatively secure in the knowledge that those cards will by virtue of the resource system only be played at an appropriate time for the cost, which consecutive turns growing to more and more powerful cards as the level of resources available to players goes up. Unfortunately, this is not a luxury that we have in AGoT. Since the level of resources per turn is so unpredictable from the R&D viewpoint, there isn’t a built in pressure valve to the resource mechanic that keeps the most power effects from being played later in the game. Even an army with a huge effect priced at 8 gold could be played on the first turn in AGoT, while that would normally have to wait until the eight turn at the earliest in MtG.

The level of draw in AGoT also directly connects with the resource issue as well, however. Not only are expensive and powerful cards impossible to predict in AGoT, but as well, smaller, more incrementally efficient characters are able to be pumped out at much faster speeds. While the early turns of MtG are generally restricted to one creature per turn with a incremental increase in power level, or in the midgame once resources have built sufficiently to allow for the play of two smaller characters, the continued play in these lines is actually quickly restricted by draw. As draw is so much more restricted in MtG, players must more actively manage their handsize and rate of play compared to AGoT in order to not play out their entire hand and leave themselves with no options. The high rate of draw and variable resources in AGoT, however, means that a large stream of smaller, efficient characters can be played from turn one and steady play maintained for more turns, leading to the possibility of much more quickly flood boards.

The final core mechanic of AGoT that needs to be examined is combat. Again, we’re going to compared to MtG where creature based combat is a 1v1 joust type mechanic. While multiple attackers and defenders can be declared, each one is generally fighting and dealing damage singly to the opposing creature. This damage each combat then can lead to the death of creatures. The attrition rate of combat is potentially quite high then as creatures attack and block and as the overall power level of the creatures go up each turn. In AGoT, however, creatures attack en mass, which prevents such a direct level of interaction and leads to a much lower attrition rate. If I attack with 2 Lannisport Weaponsmiths and the opponent defends with two Refugee of the Isles, we only compare their aggregate strength on each side and then barring card effects, the defender only kills characters equal to the claim of the attacker. Since the standard claim is generally 1 and the choice is made by the defender, the least valuable single character is killed each turn, which means that characters are killed of much more slowly than the several that are played out under our draw and resource schemes. And that, of course, only accounts for the military challenge. Since AGoT also offers two other ways to attack (intrigue and power) characters are often diverted to participate in those challenges instead where no characters at all leave the table due to the base mechanics of the game, which further lowers directly destructive combat interaction ala Magic.

So where does all of this leave us? Playing a game whose multiple levels of mechanics lead to a rapidly expanding board state and an ever growing character base. Very quickly this reaches levels where the math involved in the give and take of AGoT challenges reach levels that the average gamer quits wanting to pay attention to, or attempt to pay too much time calculating ever possible convolution and leading to a situation commonly known as “analysis paralysis.†This is, of course, assuming that the board states are roughly equal. Due to the random draw of the game, it is still possible for one player to have come out to a large and commanding lead on the board which the other player is reeling too hard to recover and stabilize from.

Enter Valar Morghulis. A plot card so integral to the game now, that it’s used as an effectively evergreen way to offset the core mechanics of the game that would actually unbalance their own gameplay over time.

And the really funny thing? It wasn’t even in the very first set of the game back in 2002.

- mischraum, Reager and Zouavez like this

Sign In

Sign In Create Account

Create Account

10 Comments

Are there viable decks without valar (morghulis)? And if yes, do they substitute it with something similar like Wildfire Assault (Core)?

I bet I could wreck most of my play group by using a Valar offensive deck instead.

@Ire & WarrenC, Agreed. I wasn't intending to say through the articles that all decks should inherently be required to play it and in fact, I often find myself swapping it out for Wildfire or the like in order to experiment. I think it's a good thing to have other plot options, high claim, or event options like Westeros Bleeds because they all pull toward different strengths. I do feel, however, that the game is balanced on Valar's existence and legality of play, regardless of whether or not everyone does actually use it themselves.